But while a relief to many after Ishiba, she is not the “change candidate”. That said, it is unlikely to matter. Japan is changing anyway, whoever is the PM.

Congratulations to Takaichi Sanae on winning the LDP leadership race – and on thus becoming Japan’s first female Prime Minister. In that aspect, her victory certainly reflects a positively changing Japan. Moreover, as the self-anointed heir of the late Shinzo Abe – the ultimate “change candidate” back in his day – she offers the LDP, and the country, some hope of restoring the positive aura of the “Abenomics” era, before it was diminished by COVID and a revolving door of evermore feckless successors. And on that basis too, Takaichi represents a positive change when compared to the current (and arguably most feckless) leader, Shigeru Ishiba, (who arguably should never have beaten Takaichi in the same contest last year).

But… When cast against who she won against on Saturday – specifically, her main rival Shinjiro Koizumi – Takaichi’s victory will be seen by many as a reaction against change – indeed even as a victory for ‘old Japan’ over ‘new Japan’.

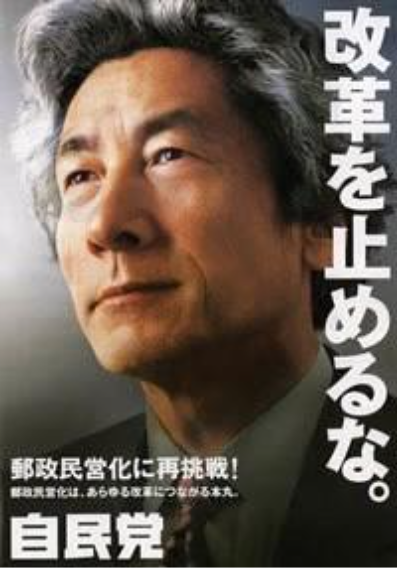

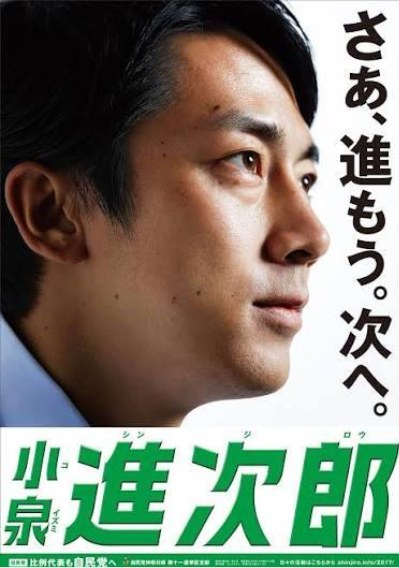

For starters, while Takaichi hopes to channel the aura of Abe, Koizumi’s aura for many literally embodies that of his father, former PM Junichiro Kozumi (2001-06) – the OG of “change candidates” – who even selected the young & untried Abe as the custodian of his radical reform agenda back in 2006 – a role that Abe failed at the time to fulfil (caving-in to ‘old school’ factions within the LDP). Koizumi senior was more popular than Abe ever was – and his is a powerful legacy.

While the son is not the father, image is everything in Japan. And the younger Koizumi looks, speaks and acts like his dad – and even his campaign slogans and posters look similar (see pictures below). In last year’s LDP leadership campaign, he even used「聖域なき規制改革」(“Regulatory reform with no sacred cows.”) - a direct lift of his dad’s most famous and era-defining catch cry「聖域なき構造改革」- (only replacing the word “構造” (structural) with “規制” (regulatory)). While he watered that down a little this year, his policy manifesto still wasn’t shy of using the word 改革 (reform) explicitly, including calling for「大胆な規制・制度改革」 (“bold regulatory and institutional reforms”) and even「自民党改革」 (“LDP reform”) echoing his father’s famous battles to modernize his own party.

By contrast, Takaichi’s campaign avoided the word (reform) altogether, focusing instead on immigration, security, and constitutional revision, while vowing to continue fiscal and monetary stimulus. While it is true these issues mirror those of Abe, her emphasis seems to be more on the national security issues than the economic ones – while she has so far failed to commit to the one arrow (from Abenomics’ “three arrows”) that the economy arguably still needs most – that which called for 構造改革 (structural reforms).

Like Father, Like Son. Campaign Posters of Junichiro Koizumi (2005) and Shinjiro Kozumi (2025)

改革を止めるな。」“Don’t stop reform.”

「さあ、進もう。次へ。」“Let’s move on. To the next.”

And then there is the difference in “age” – or, more importantly, in “generation”. At 44, Shinjiro Kozumi is a full 20 years Takaichi’s junior. Whatever his policy platform is, that age puts him squarely within that demographic cohort of those born after 1970 who’s life experience in adulthood - thanks to the 3 decades of post-bubble deflation and malaise - has been starkly different to that which Takaichi reflects. And as I argued in my previous note (#1 - here), that difference in life experience is key to explaining the different attitudes towards reform between the generations. Just being of that post-1970s cohort means a lot.

Finally, on foreigners and immigration too – the embodied contrast is stark. The sharp rise in numbers and influence of foreigners in Japan has been one of the more visible and, for many Japanese, confronting changes here of recent years. And so it’s no surprise that it was a core issue during the campaign, requiring all candidates to address it. Koizumi – who is famously married to a “French-Japanese” former TV announcer (Christel Takigawa) – promised little, other than to ensure visa programs would be “not without limit”. Takaichi, by contrast, suggested she may “suspend and review policies that bring in people with different cultures and backgrounds every year.” While these comments sparked attention – and even concern for their potential negative economic impact – most of the visa policies she is referring to were actually brought in during the Abe administration, and for various (demographic and economic) reasons, are unlikely to be curtailed in any meaningful way. [To be addressed further in a future note.]

So, what does it matter? Probably very little. In conclusion, while the above points suggest that Takaichi may not be the “change candidate” some reformers had hoped for – it probably won’t matter. Her victory is unlikely to significantly slow the pace of actual reform – or change. This is because Japan is reforming rapidly anyway – and its largely not being driven by politicians, but rather at the level of the bureaucracies – the ministries, regulators and related agencies (TSE etc) – by a younger generation of officials (born after 1970) whose power & influence, thanks to Japan’s peculiar demographics, is only set to grow over the coming decade (as discussed last week). And even Takaichi fails, and follows the same feckless path of her recent predecessors, it seems completely probable - even inevitable - that Shinjiro Koizumi will be up next. In “old Japan” tradition, he just needs to wait his turn. [So the information on him above will still be useful sometime in the [not-too-distant?] future.]