%20(1).jpg)

Today (Mon, 29 Sep) marked the official start of the contest to determine who will be Japan’s next PM – with the result expected this Saturday (4 Oct). While focus is quite rightly on the result – and we will comment on that in turn – a glance over the pool of 5 candidates allows a brief, but broader observation on the importance of Japan’s peculiar demographics on who holds decision-making power in this country.

If they were employees, not politicians, most would have to retire. Of the five candidates, all but one (Motegi, born 1955) would become the most recently-born PM in Japan’s history if they won – with the most-recently born PMs to date all born in 1957 (Ishiba, Noda and Kishida). But despite this, 3 of the pool – Motegi, Takaichi and Hayashi (both 1961) will still be entering the top job at or above the age at which almost all other Japanese citizens are mandatorily required to retire. The other 2 - Kobayashi (1974) and Koizumi (1981) - are both born after 1970.

Ok, but so what? It’s certainly not unusual for politicians in any country to be above the retirement age – and just like most countries, politicians, company directors & executives and government-appointed boards etc (like the BOJ Board) all have no formal retirement age cap. For everyone else, however, the limit is 65 or below and, importantly, for public servants within Japan’s vast bureaucracy, it is 62 (up this year from 61 in FY2023, and to be raised gradually to 65 by FY2031).

Why this seemingly trivial observation matters in Japan is because of how the country's seniority-based system of career promotion intersects with; (1) the extremely pronounced two-humped pattern of Japan’s post-war demographics; and (2) the stark contrast between Japan’s pre-bubble and post-bubble periods.

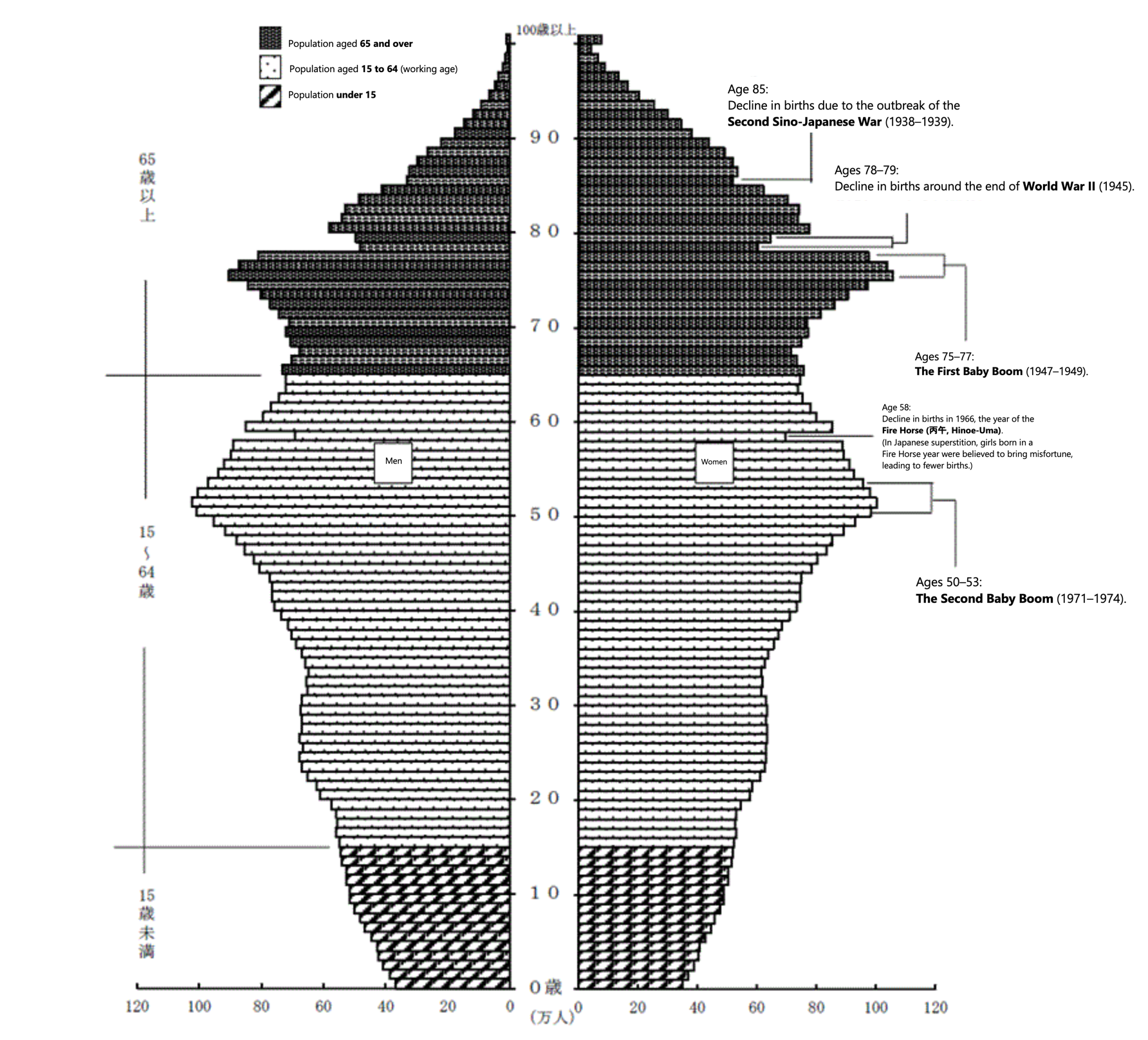

Two distinct humps, two completely different life experiences. As most already know, the disruption of WW2 and no immigration, saw Japan’s post war age pyramid exhibit two very distinct bulges - or humps - the first reflecting an explosive baby boom in the immediate post-war years (~1946-50) – and the second reflecting when those “boomers” all had kids (“juniors”) of their own (~1970-75). In no other country are the two humps so prominent nor, importantly, are the life experiences of those within each hump so starkly different. And that difference is crucial to understanding how demographics is driving change in Japan right now.

While the original "boomers" entered adulthood into booming growth, successful industry policy, life-time job security, and soaring asset inflation, the “junior” generation entered theirs just as that bubble burst; turning 20 through the early 1990s, looking for their own lifetime employment precisely at the onset of Japan’s “lost decades” of prolonged debt deflation and malaise, exacerbated by the sequential crises of the Y2K-bubble burst (2000), the GFC (2008) and Tohoku earthquake & Fukushima (2011). That timing, and not merely age, explains a huge difference in attitude among the “junior” generation versus that of their parents. And that change pivots around a birth year of around 1970.

Figure: Japan's Population Pyramid (as of October 1, 2024)

(Source: Statistics Bureau population pyramid, 2024 estimates https://www.stat.go.jp/data/jinsui/2024np/index.htm.).

So where are these two generations now? In 2025, the original "boomers" are now all but retired (albeit some crucially still hang on in positions of power within politics, and on corporate boards (and the BOJ board)). Meanwhile, the oldest of the juniors are just turning 55 – so are just entering the most crucial 55–65 bracket ; the final decade of official employment when Japanese organizations concentrate real managerial and policy authority (the 部長→役員 pipeline). So, finally, this ‘long lost’ generation – more comfortable with uncertainty, cynical of the ‘miracle’ of their parents’ generation - can now act on their frustrations. And their influence is already becoming clear.

This empowered "junior" cohort is now driving reform. Among regulators and bureaucrats – where power is most concentrated in the 55-65 age bracket - we are already seeing a wave of reform initiatives including on governance, TSE capital-efficiency pressure, clearer M&A/TOB guidelines, among others. And this is just the beginning. As their hump slides from 55 through to 65, the next decade of reform is increasingly in the "junior" generation’s hands.

Corporate management is changing too – but still lags. Recall that company directors and C-suites – like politicians – can stay on beyond 65. And in many instances, they stay well beyond. Research suggests that across listed large caps, the average CEO's age is still well above 60 while the average board chair is above 65 – with many in their 70s. This suggest that still only a minority of CEOs are born after 1970. But this too will inevitably change, and there in lies reason for optimism.

Last week, my colleague John Fou observed in a note – (Owner-Led Advantage in Japan: Evidence and a Harder Path to Change) – the data suggests that founder/owner managers deliver far higher ROE and their companies trade at materially higher PBRs than those run by career directors without ownership. It's easy to imagine a similar effect exists between companies managed by members of the “junior” generation and those by older cohorts.

So, in conclusion, while Japan’s aging demographics is a well-worn trope – and no doubt will be rolled out again this week in the context of who Japan’s next PM will be, it is often misunderstood why exactly it matters so much – and how a difference of only a decade or less between cohorts can have so much impact.