Takaichi may not have been the “Reform Candidate” – But she is the “Reflation candidate” - and Inflation is the Ultimate Reformer.

This note is a sort of addendum to my earlier note (#2) sent following Takaichi Sanae’s victory in Saturday’s LDP leadership race. In it, I made the point that while becoming Japan’s first female Prime Minister certainly reflected a positively “changing Japan”, Takaichi herself, was not really a “change candidate” - and indeed in many respects hers was a victory for ‘old Japan’ over ‘new Japan’. And her cabinet selections since would seem to confirm that.

So how does it make sense then that an “old Japan” reactionary might warrant such a bulled-up market reaction – with both NKY and USD/JPY ripping to period highs? It begs the question, how would have markets reacted if the more-bonafide “change candidate”, Shinjiro Koizumi, had won? As I argue below, probably not as much actually…

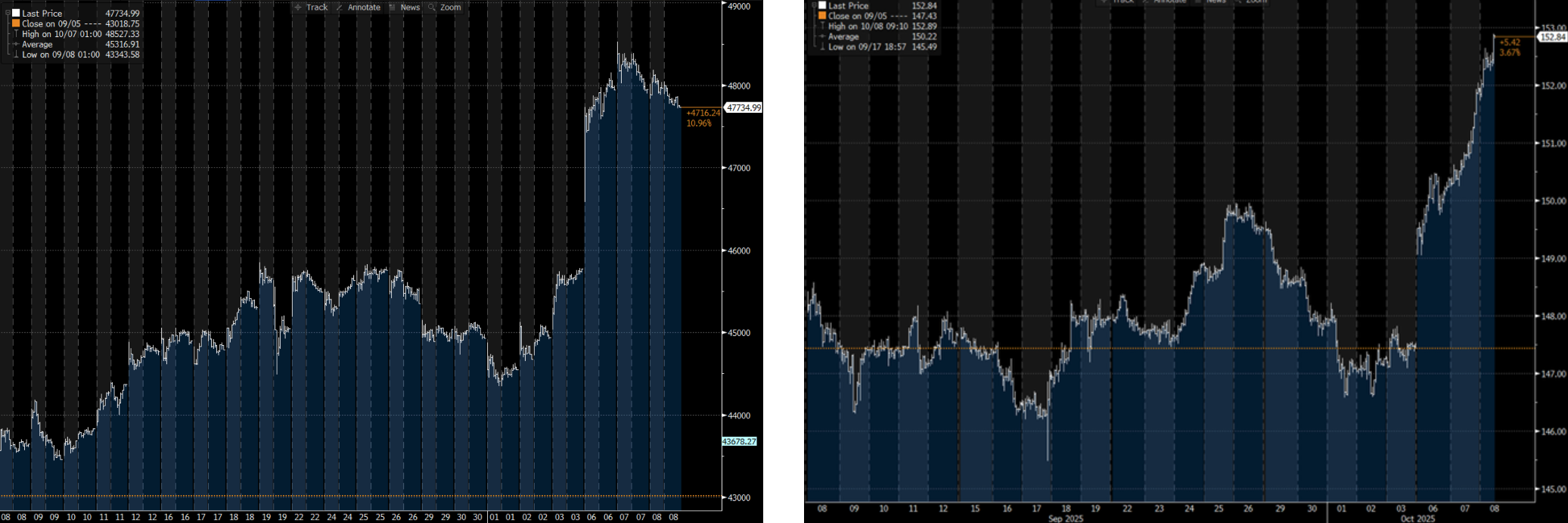

Japanese stock prices(NKY225) - and USD/JPY ripped on Takaichi’s win

For me, these sharp moves reflect the power of inflation. While Takaichi may not be a big “reformer” in the conventional sense, she certainly has the bonafides over Koizumi as an Abe-style reflationist. Indeed, the foundation of her “Sanaenomics” are further pro-cyclical fiscal and monetary stimulus. And reflationary policies are indeed bullish for NKY and USD/JPY.

But one wonders if she has quite thought through the implications. For once embedded, inflation can prove a far more powerful engine of “reform” than anything the youthful Koizumi might have envisioned in the「大胆な規制・制度改革」(“bold regulatory and institutional reforms”) he laid out in his policy manifesto.

Inflation is the ultimate disruptor. Inflation, at its core, acts to punish inaction, penalize delay, overturn the status quo, reward speed, and force prioritization. And it operates everywhere at once. Under its power, economic agents - households and corporations - are suddenly forced to act or be left behind.

Under deflation, wages and prices stick; cutting nominal pay is taboo, raising prices is reputationally fraught, and “absorbing costs” becomes a managerial virtue. With inflation, however, relative prices and wages can move without breaking taboos. Shuntō deals clear at higher levels; services firms change their prices earlier in the year; managers learn to talk about pricing power without embarrassment. None of this requires new legislation, policy reforms. It happens naturally, but pervasively.

Inflation changes how companies think and act. When prices rise and nominal cash flows follow, leverage makes sense, hoarding cash doesn’t. The same firm that clung to net cash for safety should rationally migrate toward a net‑debt position - locking in long‑dated funding while real liabilities are gently eroded by nominal growth. A generation of deflation explains net cash and fortress balance sheets. Inflation fundamentally changes that accounting. Cash needs to be used - driving buybacks, capex, M&A, productivity. Households, too, need to reassess in the same way. In both cases the direction is the same: away from hoarding and saving, toward leverage, investment, and balance‑sheet urgency.

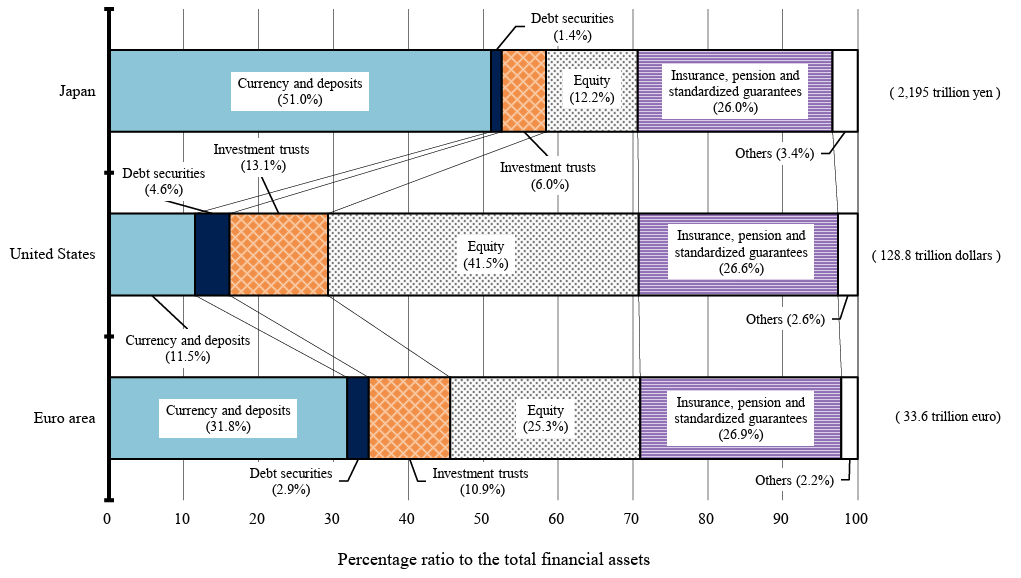

As every investor in Japan has heard repeatedly, decades of deflation has left households (by comparison to their US and EU counterparts) notoriously under-invested in risk assets, instead wildly skewed to cash and deposits - a structure that made perfect sense under deflation. Inflation radically overturns that. But it takes time to change investor mindsets after 30 years of deflation. Despite huge reform efforts by Japanese financial regulators, the TSE and the government to improve the function of Japanese equities markets and to incentivise households into invest (NISA etc), the percentage shift from cash into equities among households has been only 3%pts between the 2020 and 2025, leaving the overall percentage in equities only barely into double-figures. But it is changing. It’s no longer just NISA or TSE reforms. Inflation is changing mindsets. And the sums are huge. At total household financial assets of ¥2,195 trillion, each 1%pt shift represents almost $150 billion, and look at the gap to even just EU households…

Japanese household financial assets still wildly skewed to cash & deposits after 3 decades of deflation – Comparison with US, and the EU (As of end March 2025)

So in sum, this I think may explain why markets have reacted so positively – maybe even structurally - to Takaichi’s win, despite her overall “Old Japan” vibe. After an entire generation of deflation and stagnation, the reform-like change that could come from another reflationist push at this time could dwarf those from any of Koizumi’s imagined “regulatory and institutional reforms”, no matter how radical. Given Takaichi’s anti-reformist rhetoric, one wonders, however, if she quite gets the full implications of what Sanaenomics may indeed unleash… I suspect not yet. Beware a sudden change of heart.